The Repentance Grift

How Platforming Former Extremists as “Experts” in Deradicalization Causes More Harm than Good

On an ashen March morning in Montreal, Canada, seven people sat around a boardroom table – four former white supremacists (myself included), one ex-Jihadist and another dialing in on speaker phone, one inner-city ex-gangbanger, and a partridge in a pear tree. For two days we drummed up strategies for disengagement and counter-radicalization…or so we tried. It was a rare experiment facilitated by a transatlantic partnership between two government-funded Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) think tanks, one Canadian and the other UK-based: throw a bunch of former extremists together and see what valuable insights could crystalize in the ensuing discussion. So we discussed, while academics watched the spectacle unfold and took copious notes.

After a brief debate over the term “Formers” as the catch-all label used to describe reformed extremists, we spent the rest of the day tackling the most persistent issue – how to rebrand our pasts into lucrative futures despite the absence of anything that might pass as a track record. I was the only former in the room with a criminology degree, though neither myself nor the others appeared to have any deradicalization street cred. Sure, the lot of us had given plenty of interviews, but despite our press clippings and the odd attempts to dissuade extremists away from radicalization by way of Twitter or Facebook exchanges, none of us had “deradicalized” anyone. At least not tangibly; who knows, maybe some violent radical had seen our cautionary tales on television and realized the error of his ways, falling to his knees in self-flagellation and regret. Maybe all those TED Talks and front-page articles made a difference. But I suspected otherwise.

Over an hour was spent complaining about not having certifications on the wall to validate how capable we were. Someone suggested teaching CVE workshops in prisons as a way to leverage our abysmal credentials. Sure, I was game. As an undergrad student I’d volunteered in prisons, the bulk of my time consisting of arts-and-crafts and nail-painting sessions with female prisoners. The most exciting thing that happened was when an inmate stole a pair of scissors from the manicure bin and the COs locked down the entire wing until the scissors were retrieved. Nevertheless, our individual experiences as former extremists, married up with a marathon of OZ or Orange is the New Black, seemed like a fine way to demonstrate our prowess as deradicalization experts.

We were handed fancy Moleskine notebooks and, just as one does upon signing up for a Multi-Level Marketing scheme, encouraged to compile a list of reformed extremists we could invite to join to our fledgling global movement of formers united in the noble pursuit of countering violent extremism. I failed miserably; two decades had passed since my defection from the far-right and I had no contacts to tap. A few names were thrown around the room but quickly shot down. One could’ve been great, save for a serious drug addiction. Other proposed recruits had personality problems or criminal records that barred them from crossing international borders.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a keyboard shortcut we could use as a slogan,” said the only other female “Former” in the room. “You know, like let’s Control-Alt-Delete hate.”

“Maybe we could do something with the Shift key”, I offered.

“Oh yeah, like shifting away from hate. We could be, like, Shape-shifters.”

I snuck a peek at the academics briskly jotting down our pearls of wisdom and secretly wondered if they were getting their money’s worth, or whether this meeting – the flights to Montreal, fancy hotel rooms, pricey restaurant outings and photo-op press conference that would follow – was simply a tax write-off for organizations that received millions in funding to distill the magical elixir that would end radicalization.

They hadn’t a clue that among us experts, the ex-jihadi and the gangbanger scored drugs from some guy in the hotel lobby and spent most of last night stoned out of their minds, while the rest of us got drunk in one of the rooms and gossiped about our sordid pasts. The gangster kept pointing to his leg, where an embedded bullet fragment bulged from his shinbone. "Go ahead, touch it, go ahead", he insisted until we all obliged, to be outdone only a moment later by one of the ex-Nazis showing off a nasty scar incurred in a stabbing.

As Formers, we were the exotic factor – human data points ostensibly fetishized by researchers eager to place us under a microscope lens and dissect our psychological processes in order to extricate an antidote to terrorism.

But could we give them what they wanted?

Just six months earlier, the United States was rocked by graphic images of violence that erupted when the now-infamous Unite the Right rally brought together hundreds of white nationalists and racist militias in Charlottesville, Virginia and culminated in the killing of counter-protester Heather Heyer. The mainstream media bent over backwards to interview white supremacists in an effort to provide a “both sides” narrative – but given the dubious ethics of platforming current fascists, reporters quickly turned to formers who opined on the grievances and alienation fuelling the burgeoning alt-right movement.

Predictably, a speaker’s market was created overnight for former extremists who had an insider’s story to sell and financial incentives to leverage tales of hate and violence swathed in remorse. Formers previously ignored by mainstream media were suddenly featured on CNN and a myriad other TV specials. One American former neo-Nazi’s going rate was $7500US plus flight and accommodations for a one-hour talk – I learned of his fees after event organizers from one university that sought to book him balked at the expense and hired me for a fraction of the cost demanded by his agent.

It was a feeding frenzy of epic proportions, a veritable goldrush for former extremists. Everyone I knew was fielding phone calls from journalists desperate to source neo-Nazis for soundbites, or filmmakers trying to option movie rights. Within months, organizations headed by formers who spent most of their time soliciting donations and positioning their relevance rather than rescuing wayward youth from the clutches of fanatics, started getting tons of media coverage because they claimed they could curb radicalization by helping people leave hate movements. Huge government grants soon followed, despite the fact that their CVE programming lacked transparency and “clear metrics to evaluate impact or measurable results” and tended “to be built on poor conceptual and empirical foundations”, or what the Brennan Center dubbed “junk science.”

Behind the scenes, some formers still appeared to adhere to the ideology they professed to reject. In July 2020, Matthew Heimbach, an American neo-Nazi who purportedly left the white power movement soon after facing legal troubles stemming from his involvement in Charlottesville, ran a webinar aimed at fighting extremism but in the comments section praised Romania’s Iron Guard leader Corneliu Codreanu, as well as Nazi-era ‘degeneracy laws’ used to imprison gay people. In another case, an ex-neo-Nazi showed me text messages from an ex-Al Queda member who intercepted a request from a young girl seeking assistance in escaping a white supremacist gang; instead of helping, he flirts with her and brags about his terrorist past and how he knew all about fission.

No evidence exists to show that a violent extremist has ever been deradicalized by a TED Talk, and I’m not aware of any victim of racist violence who earned $7500 to speak about their victimization. The majority of people who believe speeches by former neo-Nazis make any difference in terrorism prevention are unlikely to have been victims of hate crimes. One would have to be pretty naïve to imagine that we were making an actual difference, but sticking to the narrative was profitable enough for those who had few, if any, other prospects. And so we plodded on.

It’s hard to make an income as a former neo-Nazi, and I’m pretty sure we convinced ourselves that we were doing good. After all, what was the harm in platforming former extremists as role models who exemplified a way out? We didn’t create this fetishization of fascism. Without journalists and academics keen to lap up our stories and monetize them through clickbait articles and fundraising proposals, “Formers” would not have been rebranded as rock stars. And since reporters, PhD students and thinktank directors were coming at us with relentless interview requests, surely were sitting on a valuable, marketable commodity – our extremist pasts.

When the opportunity arose to be interviewed for a role as one among a handful of Regional Coordinators for Central Canada and the US at a global network of former extremists, I jumped at the chance. The UK-based program director happened to be in New York City at the same time I was there for a talk at Columbia University alongside an ex-Taliban member, and it seemed like kismet that we’d crossed paths. I was beyond thrilled to join such an illustrious project and terribly impressed with the prestigious European organization that had created this initiative.

Regrettably, the death knell of my promising new career came in the summer of 2018, less than six months after that first Regional Coordinators meeting in Montréal. I was on a conference call with the same team of formers when the discussion shifted to an ex-skinhead newly released from prison who was keen on becoming a speaker. “But he’s not ready yet,” said the program director. "We’ve got to work on his antisemitism."

In that instant, my past and present collided with a bang. All my unspoken fears materialized: there I was, a Jewish lesbian partnered with a woman of colour, trying unsuccessfully to convince myself that my work didn’t pose a risk to me or my loved ones. My mind started racing: Maybe I’m not cut out for disengagement. How can we be sitting here, trying to help an antisemite become a public speaker? We’re not deradicalizing anyone; we’re just marketing formers as CVE experts. Would I want this guy in my home? If not, why would I want him at my synagogue? And why would an antisemite want to speak at synagogues anyway? Does he think we’re all made of money?

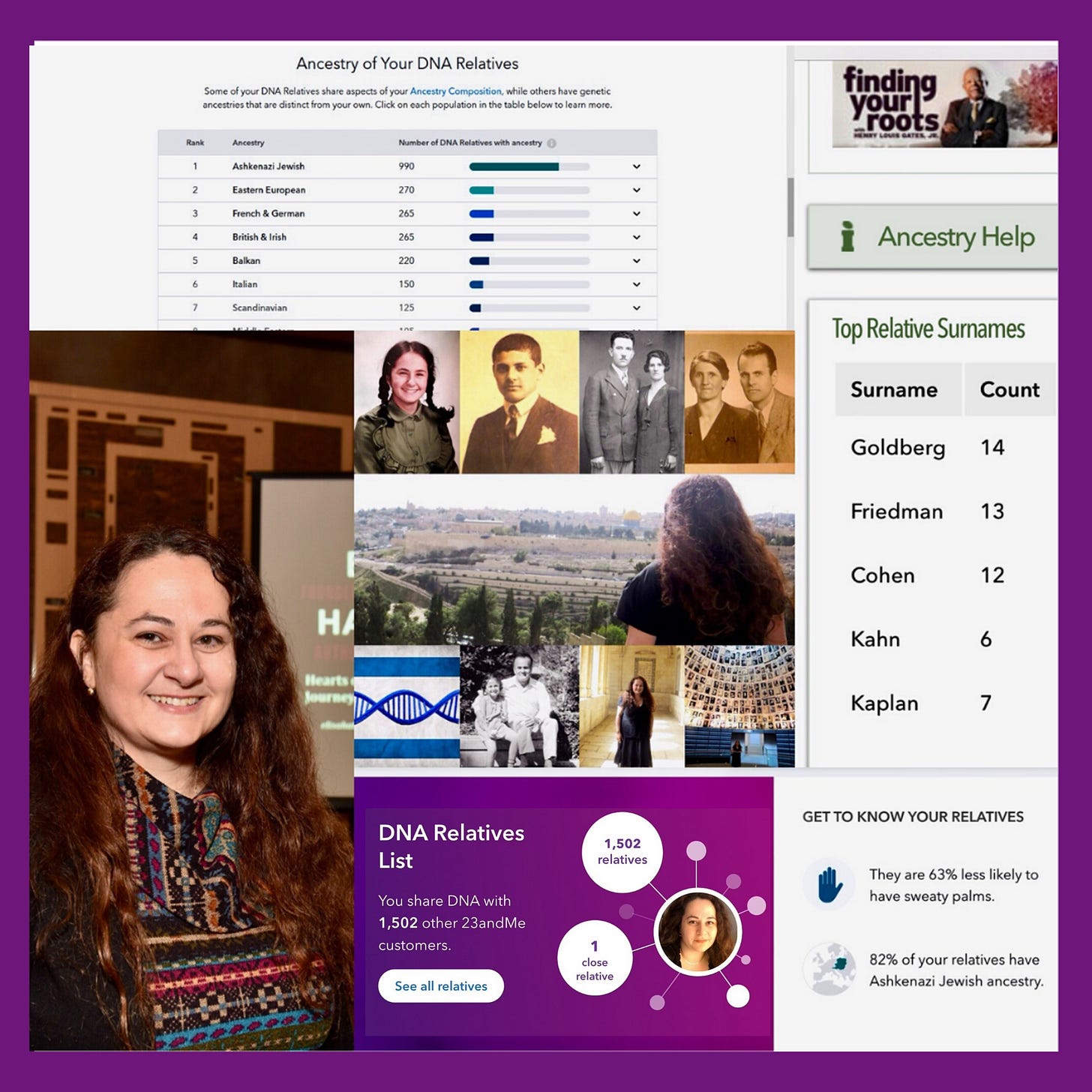

I remembered all the kind people I’d met while working with Jewish organizations, fellow synagogue congregants and friends who invited me into their homes for Passover seders because I have no family in Canada and holidays are difficult for me. Relationships I’d forged with Jewish cousins through 23andMe and Ancestry. I didn’t want them potentially exploited by an antisemite with an assault record peddling his repentance shtick to the Jewish community.

My community. My people. My loyalties lay with them, not with this ragtag, scattershot bunch of circus freaks. And that realization came despite knowing that yes, I was a freak too.

I emigrated to Canada from communist Romania in 1986, when I was 11 years old. I was the unwanted, only child of deaf parents, and my childhood was marred by neglect, physical and emotional abuse. My father died after I turned 13, and by the time I was 14 I was living in Children’s Aid group homes and foster care. Eventually I ran away from a foster home and went back to live with my mother, dropping out of high school in grade 9. We lived in a low-income Toronto housing project where shootings and drug abuse were rampant, and I felt alone and alienated. I missed Romania and my best friend, whose family had looked after me whenever my father locked me out on the streets as a child. Like many first-generation immigrants, I had a hard time adjusting from a totalitarian upbringing where individuality was suppressed, to a society where diversity was not only encouraged but expected.

My search for identity, coupled with my teenage angst and nostalgia for my lost homeland, led me into the arms of a new “family” that exploited my vulnerabilities and groomed me to become the female face of their movement. At age 16, I was recruited by Canada’s largest white supremacist group in modern Canadian history, the Heritage Front. I gave speeches at rallies and represented them in newspapers and television interviews, culminating with me appearing on The Montel Williams Show to represent Canada’s far right alongside the son of Tom Metzger, leader of White American Resistance (WAR). I was just 17 years old and Front leaders had forged my parental consent waver.

Within a month of my recruitment, I became the errand girl of notorious German revisionist publisher Ernst Zundel, who became like a grandfather to me and allowed me to stay at his place whenever my mother’s abuse escalated to blows. Zundel convinced me that the Holocaust was a hoax and introduced me to international antisemites like David Irving and Fred Leuchter, fellow proponents of Holocaust revisionism. Behind the scenes, I was taught to fire guns in preparation for a “race war” where we would have to defend ourselves against a purported ZOG (Zionist Occupation Government)-planned white genocide. However, it was the Heritage Front’s escalation to targeting innocent people – specifically, anti-racist LGBT community activists – as part of a concerted harassment campaign that broke the spell and made me question who I had become.

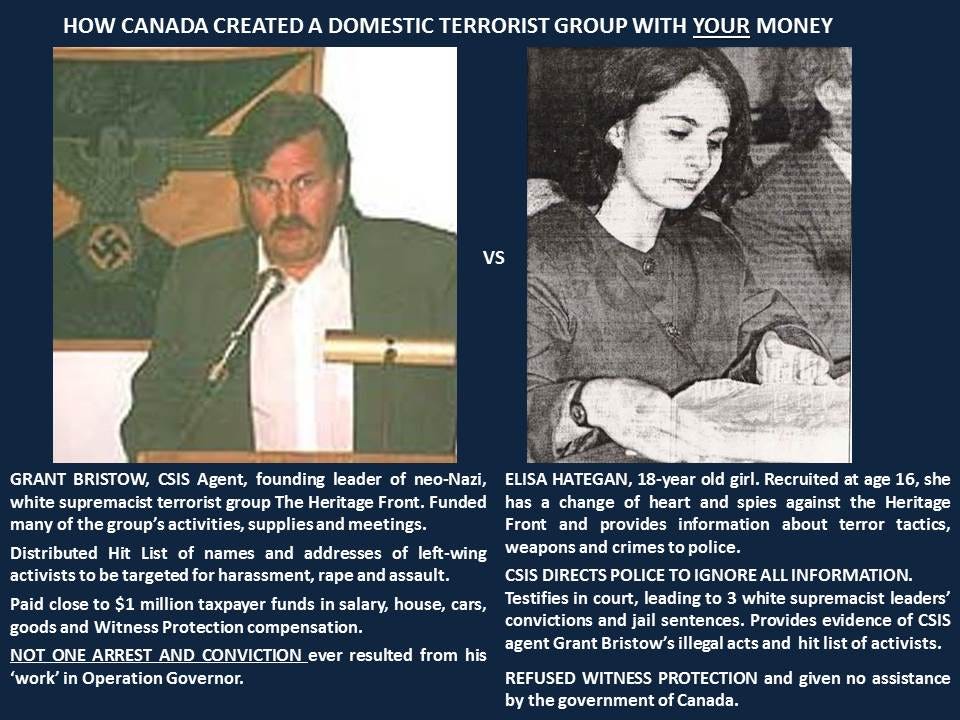

At age 18 I came out as a lesbian and defected from the group, turned over 30 affidavits over to police, exposed a Toronto police officer as a Heritage Front member, exposed criminal activity by CSIS mole and HF founding leader Grant Bristow, testified against 3 leaders who were sentenced to jail as a result of my testimony, and was instrumental in shutting down the Heritage Front. I lived in hiding all across Canada, switching cities as easily as I discarded aliases, running from death threats while struggling to understand what had happened to me, how people like me could be so easily seduced by hate. At 19, I was accepted as a mature student into the University of Ottawa’s renowned criminology program, and in 1999 I graduated magna cum laude with a double major in criminology and psychology.

Years later, I learned that my father’s family was Jewish and I’d had relatives who perished in the Holocaust. In my childhood there had been clues and rumours, such as my grandmother (who died when I was 10) never mixing meat and milk, and telling me that when she was young, our family’s day of rest was on Saturday rather than Sunday. As a teenager, when confronted by neo-Nazis who accused me of “looking Jewish”, I denied it, suppressing my identity to stay safe. However, a 23andMe DNA test in 2012 conclusively confirmed my ancestry. This discovery precipitated my conversion to Judaism in 2013 – I was reclaiming my heritage, stolen from me by centuries of eastern European antisemitism and pogroms that had forced my grandparents to hide their religion and ancestry.

After what I’d undergone as a teenager, I would be lying if I said that I didn’t compare the red-carpet treatment other formers received to my own lackluster experience. Unlike the formers who struck gold in the post-Charlottesville rush to turn extremists into role models, I had put three white supremacist leaders in jail, helped to shut down a violent hate group co-founded by a CSIS agent, and lived in abject poverty for years. I panhandled, lived in women’s shelters and resorted to dumpster-diving to feed myself, all the while dealing with PTSD and trauma, and was never offered a book or movie deal. I have a degree in criminology, but my average honorarium is $200. Meanwhile, higher-profile ex-white supremacists who never formally studied crime secured book/film offers and large honorariums to offer perspectives informed mainly by personal experience, which ended up universalized and projected as “expertise”.

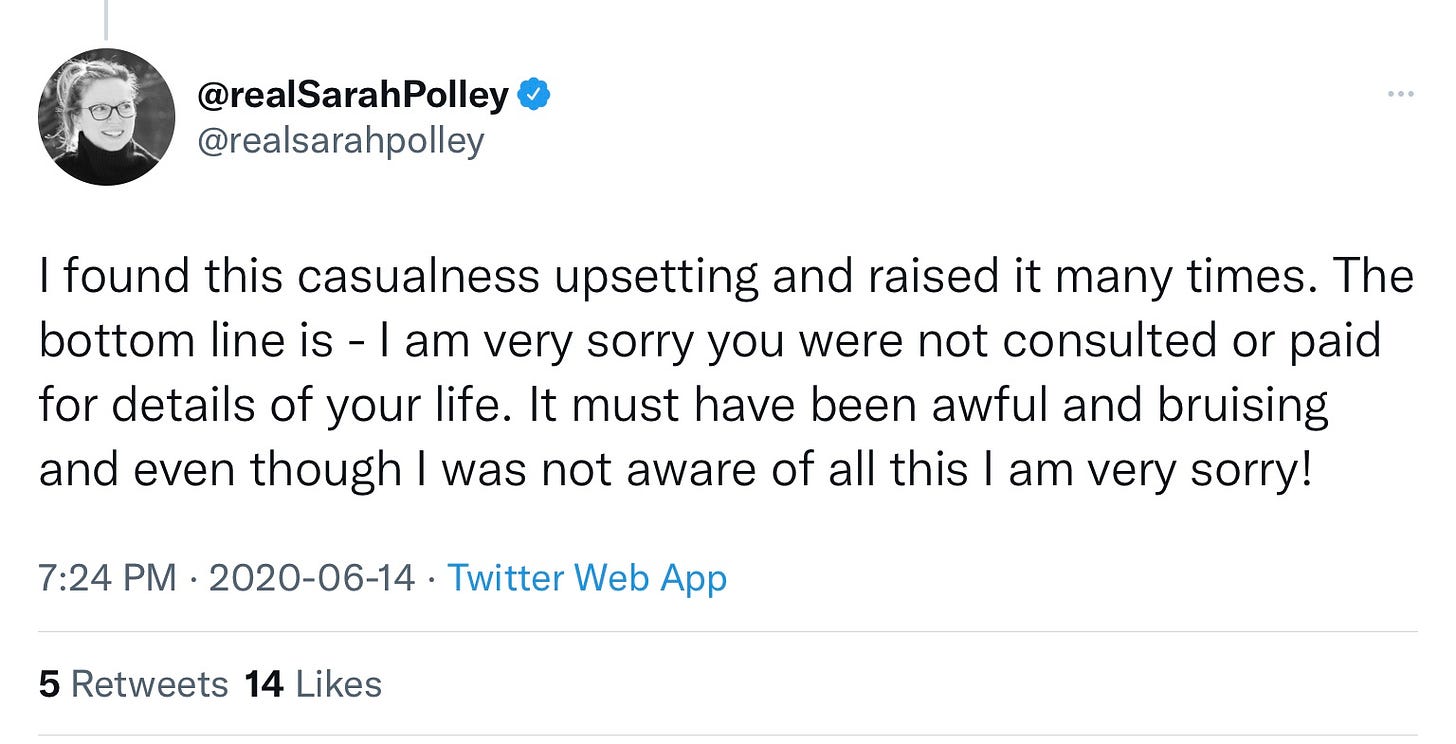

Although Penguin Canada was initially interested in my 2014 memoir Race Traitor, in the end I published it alone. And not only was I never offered a movie deal, but I was judged worthless and insignificant enough to exploit with impunity. In 1998, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation released a movie titled White Lies, starring Sarah Polley, based in majority of my lived experiences; approx. 80% of scenes can be traced and verifiably attributed to me. Some scenes recreate traumatic events almost verbatim, including but not limited to my Montel Williams Show interview, my speaking engagements, a school essay, a cross-burning rally, my work for Zundel, my defection and stealing of Zundel’s mailing list, and my 1993 suicide attempt.

For over a year, scriptwriter and producer Dennis Foon had researched my life, accessing court transcripts of my testimony against Heritage Front leaders and interviewing people who knew me, yet the CBC decided not to credit me whatsoever. While I was rooting for food through garbage and fearing for my life, White Lies (a movie that wouldn’t have existed without me) earned producers Emmy and Gemini award nominations. In 2020, actress Sarah Polley apologized - nobody else associated with the production acknowledged my existence. Why should they? I was garbage, “a wretched little immigrant girl”. And as I’ve said before, in this country the weight of truth depends on the perceived worth of those who speak it.

It struck me as deeply unfair that there is no rhyme or reason when it comes to rewarding “Formers”, no weighing of scales to ensure that extremists who recently left the movement won’t profit from previous wrongdoings, while those who risked their lives to assist authorities are not thrown to the curbside. Formers’ central selling point appears to be status rather than action, with male ex-leaders – those who called the shots, recruited and radicalized others – often rewarded with the greatest publicity upon their exit.

Perhaps the crux of my conflict with the formersphere rests in my inability to define the effectiveness of formers-led deradicalization efforts, and my failure to grasp the reason(s) behind the trend to overestimate their contribution to CVE. Is it their untested promise of disengagement competence? Helping researchers through self-curated interviews, speaking engagements and contrived platitudes? Scoring an MSNBC special or a Hollywood A-lister to roleplay them? Has any effectiveness been established before sizeable government grants get doled out to formers without track records, exacerbating the idea that there’s easy money to be had?

What naïve academics and event organizers showcasing former neo-Nazis seldom realize is, there is a small window of opportunity where a former is most valuable – the moment right before he becomes a “Former”. Walking away from hate without providing intel on a group’s criminal activity is a lost opportunity not worth rewarding. It’s having your cake and eating it too – by keeping your mouth shut you don’t risk backlash or threats, keep backdoor communication channels open, and still reap the benefits of the Repentance Grift.

I believe that the most important insights a former can offer is to give evidence to law enforcement about their compatriots’ criminal acts – to “rat them out”, so to speak. There’s no honour in an Omertà code. Want to fight extremism? Inform on your comrades and make every effort to shut them down. Spill the beans on illegal activities, even if you incriminate yourself in the process. Such actions would go much farther to countering violent extremism than rewarding formers with movie deals for having quit being jerks, which telegraphs the message that one can engage in hate-group activity and suffer no consequences; one can even become famous afterwards. Publishers don’t give rapists book deals because they’ve decided to stop raping. What is so special about a white supremacist who decided to stop being a bigot? Is walking away from stomping on people’s heads such a formidable feat that it must be rewarded with a TED Talk or a Hollywood reenactment?

You don’t reward people who have done NOTHING, with transforming them into celebrities. You evaluate atonement not by taking the former’s word that he is reformed, but by looking for concrete evidence that shows he is reformed. Formers radicalized to violent extremism have surely heard the talk, seen the guns, witnessed violence first-hand. If a former extremist tells you she didn’t witness criminal activity, she’s either lying or exaggerating her involvement. And I would contend there is no better confirmation of one’s sincerity than providing material evidence that leads authorities to dismantle a violent organization or terror plot.

Radical repentance – the kind of breathtaking remorse that keeps you up at night until you resolve to undo the damage you might have caused – requires facing the risk of self-incrimination, but it’s worth it because you may save innocent lives. Unfortunately, that’s the step most extremists skip on their way to the speakers’ circuit, even though a single debrief with law enforcement officials is arguably worth more than a thousand PhD student interviews.

In my work with former networks, I’ve yet to meet other ex-neo-Nazis who “ratted” on their comrades and put them in jail, so I’m a downright unicorn. But no matter how many lectures or interviews I give, there’s never any doubt in my mind that testifying against the men who indoctrinated me, stealing their membership lists and giving police 30 affidavits detailing weapons and illegal activities, will always be my biggest contribution to countering violent extremism.

Sometimes residents of ivory towers are so far removed from the frontlines that they're predisposed to accept any narrative as truth if it comes from a boots-on-the-ground source. Eager to find research subjects, a criminologist can easily overlook the shared personality traits of former recruiters: they’re friendly, charismatic and disarming. After years of championing a fringe doctrine and making it palatable to new recruits, formers can size up an interviewer and sidestep emotional boundaries by telling her what she wants to hear. Reframing their backstory to make past deeds less damning and their exit more heroic is par for the course.

Personal interest, such as the need to buttress a thesis or funding proposal with field sources, can render researchers vulnerable to being deceived by unscrupulous formers looking to launder their reputations through the legitimacy conferred by academia. It is in a former’s best interest to disseminate a narrative that endorses compassion over punishment because it reduces his culpability, while painting his renouncement of extremism as praiseworthy. Deception can come in the form of downplaying harmful behaviour, whitewashing illegal activity, embellishing one’s exploits, or outright fabrication of an extremist past, as seen in the case of a Canadian kebob shop employee arrested in 2020 for making a “terrorism hoax” after he lied to journalists and academics about having joined ISIS. Why would someone lie about being a terrorist? “You can get really famous by saying, ‘I used to be a jihadist and now I’m not,’” former jihadi Jesse Morton told The Atlantic magazine in 2019.

But conflicts of interest are not limited to formers. Nowhere has the observer effect been documented more clearly than the quantum physics experiment where, depending on what an observer expects to see, light manifests as either a particle or a wave. We see what we want to see – and if you are a member of a privileged majority, you tend to gravitate toward hypotheses that minimize your complicity in an unjust system that continues to uphold your privilege.

Barring few exceptions, nearly every grad student or journalist who asked me for an interview, and every event organizer who hired me for a talk in the last five years, was white. Eventually I grew convinced that academics and journalists who share a racial or socio-economical background with a former find it easier to empathize with "one of their own”. When your understanding of radicalism is abstract and detached from everyday reality, believing "there but for the grace of God, go I" may jumpstart the conclusion that the repentant is entitled to forgiveness.

It’s likely that people on the receiving end of racist violence are less credulous of formers’ redemption tales and more prone to ask questions that would make both formers and platformers uncomfortable. However, those wielding the power and purse-strings to direct society’s response to radicalism generally belong to the dominant social strata and are less likely to be impacted by violence targeting their race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation. Event organizers who enrich formers through lucrative speaking engagements that advance the promotion of a self-serving CVE framework which emphasizes compassion over punishment, rarely view themselves as complicit in legitimizing the speculative idea that empathy is the ultimate antidote for radicalization.

And thus the tail begins to wag the dog.

Shortly before his death, ex-jihadi Jesse Morton expressed frustration over “cognitive bias” coming from researchers: “Most liberals or the far-left have never seen a prison, been to the hood or anything...the degree of laughable ignorance amongst the experts were turning to solve the far-right, absent any degree of self-awareness or training in addressing their own cognitive bias is laughable.”

In an industry where formers exploit their pasts and scholars in turn exploit formers to fulfill their own cognitive biases, it’s not difficult to imagine how excess attention and publicity can be taken for granted by formers who have no other prospects. As long as projects keep materializing, formers are not incentivized to look for means of income that don’t constellate around extremism. Being hailed as an expert on radicalization despite lacking formal education or relevant work experience, fuels a misplaced sense of entitlement that can spiral to anger and frustration when the gigs dry up.

One prominent ex-white supremacist voiced resentment on Twitter after being unable to secure a consistent income: “I genuinely do NOT understand how I can NOT get a consistently paid position with some fucking health insurance and live in poverty facing a short-term reality of having to go back to bartending to feed & house my family. […] It is difficult to not see this as yet another example of a former being used and wretchedly discarded whenever it’s not time to parade a former in front of investors or stakeholders”.

Perhaps our formative impressions of redemption and forgiveness are shaped by our thrill-seeking, adrenaline-chasing culture. Mainstream media’s fascination with former extremists is ubiquitous in a society that regularly turns criminality into entertainment. Blockbuster movies featuring terrorists and serial killers, gory police procedural shows and true crime docuseries, all strive to conceptualize the disturbed mindsets of psychopaths, immortalizing mass-murderers while their victims lay forgotten. Perhaps this morbid fascination with extremism is driven by an audience’s desire to exert control over the unpredictable. However, while people’s need to diminish danger via understanding the criminal mindset offers a semblance of control, knowledge in itself is not prevention.

No amount of time devoted to studying terrorism will prevent a terrorist attack or harm inflicted on your community. Learning why someone wants you dead does not protect you if you come in the line of fire. Worse yet, a redemption-centered narrative whose central tenet proposes that the most effective solution to countering extremism involves offering love and forgiveness to extremists rather than demanding that they give up incriminating evidence, is not only naïve but potentially dangerous and delusional.

An unprovoked attack such as a mass shooting can be so random and brutal that it leads to an insidious form of gaslighting – in trying to reduce the likelihood of future attacks, members of targeted communities start to wonder if they could have done anything to prevent what happened. While presenting an outlet for vulnerable populations to feel they are gaining control of an uncontrollable situation by fortifying themselves with knowledge of a would-be attacker’s mindset, compassion-centered narratives feed directly into this gaslighting by subtly shifting the onus of power from the attacker back onto their victim – if only the shooter had been accepted by his peers, if only his grievances had been heard, if only he’d encountered empathy and compassion from a hated minority group, his crimes might have been averted.

Although it is not up to targeted communities to heal an extremist’s psychological traumas, redemption stories invariably feature a Eureka-like stroke of illumination whereby a member of a hated minority does something to provoke change in a former. Whether it is a Jewish doctor who tends to an injured neo-Nazi skinhead[22], a kind-hearted imam[23], or a black lesbian who befriends a white supremacist prison inmate[24], The Saviour is a trope that appears in nearly all redemption-arc narratives – a bigger-than-life figure who rescues the lost sheep from a proverbial cliff and sets them on the right path.

What gets left out of that feel-good, tearjerker ending is the question of whether, had it not been for The Saviour’s presence, would the former have continued to harm vulnerable communities. If the answer is yes, one could conclude that redemption-centered approaches form an insidious form of emotional blackmail, because they imply that POC and minority groups have a responsibility to reach out to those who pose a danger to them, lest they suffer the consequences.

Looking back to that Montreal boardroom back in 2018, I now realize we’d made a critical mistake: we saw radicalization factors as analogous across the board, from inner-city gangbanger to radical jihadist to neo-Nazi, and presumed that if the trajectories are all the same, so must be the solutions. By focusing on commonalities, we ignored the elephant in the room – the psychological processes of our indoctrination had as much in common as they diverged. Because certain vulnerabilities are shared by a majority of former extremists – abusive or broken family, poverty, bullying, low self-esteem, loneliness – we jumped to the conclusion that divergent groups of formers become radicalized via the same psychological or sociopolitical pathways, a fallacy that presumes white nationalists suffer the same kinds of indignities and prejudices that spur minority youth to radicalization.

But we were wrong. If you live in a predominantly white society that is a construct of colonialism and indigenous exploitation, joining a white supremacist group is not the great act of rebellion most racists imagine it to be. No matter how convincing the White Replacement argument might sound, you are not rebelling against oppression – you’re appointing yourself defender of the dominant culture. You are co-opting sympathy, mitigating factors, and feigning victimhood prior to obtaining a performative redemption earned through words, not action.

A child of immigrants who experiences discrimination due to skin colour, ethnicity, religion or lower socioeconomic status before becoming radicalized, is motivated by different factors than a white, middle-class teenager growing up in the suburbs with access to opportunities, education and extracurricular activities, who becomes racist in response to the growing non-white population around him and perceived loss of privilege and status. While both may be seeking a sense of belonging and validation from peers who look and think like them, the former is driven by a sense of isolation and search for identity in a society where she doesn’t feel represented, while the latter aims to defend and uphold the power of the ruling class by transforming himself into its most radical mouthpiece.

In my futile search to find a track record for formers-led deradicalization projects, I learned about the European EXIT programs first established in Sweden in the 1990s. The first EXIT center opened in 1998 and was ran by a former neo-Nazi. Within three years they were accused of accounting fraud, inflating the number of defectors they claimed to help in order to secure more government funds, using racist language, and playing white power music on center premises. In a 2014 paper, author Liz Fekete asks why past failures and complaints about the value and methodology of these programs have been airbrushed out of official evaluations. Pointing out their lack of transparency and accountability, she argues that “EXIT programs sideline traditional anti-racist structures in favour of anti-extremism perspectives promoted by former neo-Nazis who, unlike their victims, have never been at the receiving end of racist violence, and yet are now treated as experts on the roots of prejudice.”[25]

Other EXIT critics were similarly skeptical of high-profile success stories, pointing out the lack of statistics to document the success of formers-led initiatives. Bianca Klose, the director of a Berlin CVE program, expressed concern over how often former extremists with no experience or education are hired as consultants or trainers in violence prevention. “Soon after leaving the scene they are brought before the public and treated like experts, thus mixing the biographical with the professional. […] A person has not dealt with their ideology or come to terms with their actions, but way too quickly they’re invited into schools and workshops and even go on to become celebrities.”[26]

Unless a former has studied criminal behaviour, it is difficult to perceive the myriad ways in which others' trajectories into extremism may diverge from one’s own path. Any proposed solutions are informed almost exclusively by first-person experiences, and bolstered by the propagation of a narrative that invokes empathy and forgiveness as the primary way to counter radicalization. But just as giving birth does not transform a mother into an obstetrician, having a personal experience, no matter how unique, does not automatically make you an expert.

If the only thing on your resume is being a white supremacist, the only experience you have is putting hate into practice. Unless you’ve studied or worked in behavioural sciences or the criminal justice system, I struggle to comprehend how you differ from someone who had a baby and now believes themselves equipped to run a maternity clinic.

In the absence of corroborating evidence, I believe a higher benchmark should be set for those who incorporate formers’ statements into their research without fact-checking their veracity. Studies tainted by deception or accountability gaps might go on to inform future governmental policies, law enforcement practices, and be built upon by other researchers, resulting in ineffective or even damaging responses to political extremism. If there is the slightest risk that future methodologies might rise out of research built on a foundation of fraudulent accounts sourced from people with a vested interest in sanitizing their pasts, we need to reassess the value of involving formers in CVE initiatives.

Before entrusting and empowering formers to tackle hate group disengagement, we must ask whether they have the capacity to do the proposed work. Are they equipped:

1) educationally – have they undergone formal education and/or workplace training?

2) professionally – have they worked within the criminal justice system, social services, or with young offenders?

3) psychologically – have they received counselling and dealt with traumas, anger management, guilt or shame? Is there a danger they might be revert back to extremism while engaging with current extremists?

4) fiscally – when operational funding is provided, are they capable of transparent financial management?

I have strong opinions about the value and impact of formers’ contributions to countering extremism, and you can guess what they are. While I won’t argue that they should never be engaged in deradicalization strategies, it’s crucial that formers’ involvement is evaluated regularly to ensure that it meets its objectives, particularly when government grants and media coverage are involved, because these can confer an unmerited veneer of credibility and expertise. As far as I know, this is not being done. Potential risks must be weighed on a measurable scale against proven benefits in order to derive the conclusion that formers, albeit well-meaning, are not doing more harm than good.

If you enjoyed this article and wish to support my freelance work, every dollar makes a difference. Please consider dropping even a single dollar into my Paypal tip jar, or send an e-transfer to elisa@elisahategan.com .